Building Containers from Scratch

The first in a series of posts on how our infrastructure team builds containers without Docker, LXC, and rkt

By Giri Kuncoro

At the heart of GO-JEK’s infrastructure is the Cloud Computing and Container platform, which serves as a distributed systems’ foundation for application deployment. Our infrastructure serves 500+ microservices, supports 350 million internal API requests per second, and processes an average 35+ customer orders every second.

Containers have been adding value to our developers by improving the ability to isolate from other applications, create predictable environments, and to run applications virtually anywhere in our public cloud and on-premise data centres.

TL;DR: This is the first in a series of blog posts from talks we have given at several meetups, including Docker Jakarta. We will cover how we experiment on building containers from scratch, without Docker, LXC, rkt, and any other container runtimes.

As a disclaimer, we are running Docker and LXC containers on production. But as part of our team on-boarding, every engineer in our infrastructure team has to go through the experience of building containers from scratch. This is to make sure everyone understands container internals and gets good sense of debugging when issue arises in our container infrastructure.

Containers are fundamentally an isolated process (or group of processes) running on a single machine. Linux Kernel has various built-in features to enable this isolation: chroot, namespaces, cgroup, and other things.

Container Filesystem

Let’s look at the first line of a typical Docker file:

FROM ubuntu:16.04

...This line is essentially telling the Docker engine to download ubuntu version 16.04base container image from the container registry. The image is just a tarball (tape archive file, TAR), which contains something that looks like a Linux file system.

$ docker run -it ubuntu:16.04 ls

bin boot dev etc home lib lib64 media mnt opt proc root run sbin srv sys tmp usr varThe mechanism behind building this tarball itself is a huge topic which will not be covered here, but there are several tools that can help us: buildah, buildroot, debootstrap, YUM / DNF. We are going to pick DNF, which helps to build a Debian system into a subdirectory on a Linux host.

Let’s grab a Debian machine and execute DNF to build our container filesystem. The DNF command we execute below is telling the system to build minimal Debian system into rootfs subdirectory, with additional packages installation, i.e. python3, iproute, iputils, and others.

$ mkdir rootfs

$ sudo dnf -y \

--installroot=$PWD/rootfs \

--releasever=24 install \

@development-tools \

procps-ng \

python3 \

which \

iproute \

iputils \

net-tools

$ ls rootfs

bin boot dev etc home lib lib64 media mnt opt proc root run sbin srv sys tmp usr varThe resulting container filesystem (stuffs inside rootfs) looks truly like a Linux filesystem. It has everything that Linux has, i.e. /var in which system writes data to, /bin which contains executable binaries, /libthat contains shared libraries. However, notice that rootfs doesn’t have init system and Kernel, which explains why containers are sharing Kernel / OS, unlike Virtual Machines.

chroot

chroot is an operation that allows a system to change the root directory for current processes and its children. It essentially restricts the view of a filesystem for process. Let’s try to execute a shell inside the rootfs directory we have built.

$ sudo chroot rootfs /bin/bash

# ls /

bin boot dev etc home lib lib64 media mnt opt proc root run sbin srv sys tmp usr varNote that from inside this shell, we can see all the files at root directory, but these are actually the files contained inside rootfs directory on host. Once we are inside the shell, we can do whatever shell can do, run commands, etc...

# which python3

/bin/python3

# python3 -c 'print("Hello from GO-JEK!")'

Hello from GO-JEK!The shell shows python3 interpreter what we are executing is located in /bin/python3. This is actually rootfs/bin/python3, not the Python interpreter on our host. The container Python interpreter depends on the shared libraries located in rootfs/lib and other stuffs baked into our rootfs container filesystem.

Namespaces

Now, let’s try to do something interesting. On the other terminal, execute top from the host.

(From host, outside chroot)

$ topFrom inside our container, we can still see thetop process running on host.

(From chroot)

# mount -t proc proc /proc

# ps aux | grep top

1000 4421 0.0 0.7 52036 3968 ? S+ 22:13 0:00 topThis means our container is able to see all the processes running on host. And since we ran chroot shell with sudo, the container can kill the top process.

# kill 4421This is where we talk about namespaces. Namespaces are feature of Linux kernel which restrict processes to view different resources than what other processes view, i.e. network interfaces, mounts, and process trees. For example, set of processes A and B see different network interfaces.

To create namespaces, we use unshare. Unshare allows a system to selectively “unshare” resources being shared at the time. Let’s try to isolate the process tree of our container by creating new PID namespace, and rerun the chroot shell inside this. We merely need to pass --pid flag to unshare.

$ sudo unshare --pid --fork --mount-proc=$PWD/rootfs/proc chroot rootfs /bin/bash

# ps ax

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1 ? S 0:00 /bin/bash

4 ? R+ 0:00 ps axIn a Linux system, PID 1 is usually the init/systemd process, but interestingly PID 1 is assigned to our shell process instead. There are deeper discussions on what should PID 1 be in a container due to its special roles (reaping orphan child processes, etc.), but not covered in this writeup.

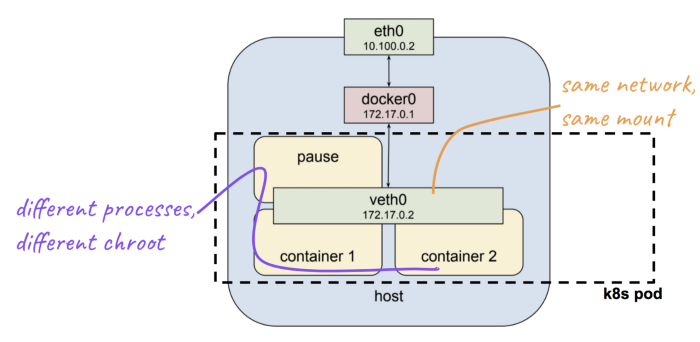

Another interesting thing to bring up — we are only isolating a process tree of our shell process, while other resources (network, mount, etc.) are still shared. Namespaces are composable, in the sense, we can choose just to unshare particular namespace, but share the others. The most popular example for this case is a Kubernetes pod, in which containers inside a pod have a separate process tree and chroot file system, but sharing network and mount namespace.

What’s Next?

Containers are basically a combination of various Linux Kernel features. Lots of topics are not covered in this writeup: how to enter existing namespace, create cgroup, container security, user namespace, copy-on-write filesystems, network namespace, inject volume mounts etc… We will continue this in the next series of blog posts, so stay tuned!

Oh, and we are hiring! Our team is dealing with Golang, containers, Kubernetes, cloud native toolings, and CNCF open source contribution. If container focused infrastructure excites you and you would like to be part of a GO-JEK Cloud Native future, please reach out on gojek.jobs .